![]()

Redan Aristoteles formulerade naturens "rädsla för vakuum", "horror

vacuui". Detta var knappast någon förklaring och långt mindre en teori för

motviljan mot tomrum. Man kunde döpa om den och kalla den rädsla, men det blev man inte

klokare av. Speciellt tydligt var att man inte kunde mäta rädsla. Rädslan var

inte falsifierbar.

2000 år senare var det dags för experimentalfysiken att hörja undersöka naturen på

sitt eget sätt. När Galilei 1632 kom med sin "Dialog om de två viktigaste

världssystemen - det ptolemaiska och det kopernikanska" framstod Aristoteles

försvar av det ptolemaiska världssystemet som mycket svagt. Aristoteles var på väg att

mista sin totala auktoritet.

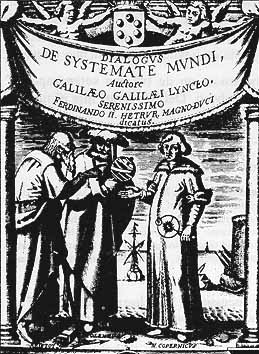

Omslagsbilden till Dialog om de två viktigaste världssystemen, utkommen 1632,

här i Leydenversionen från 1642. Aristoteles till vänster, Ptolemaios i mitten och

Kopernikus till höger.

Galilei forsatte att i samtalsform diskutera också jordiska skeenden. 1638 kom hans

"Diskussion om de två nya vetenskaperna", en bok som behandlar hans resultat

inom mekaniken. Han fortsätter att spela ut Aristoteles (nu företrädd av sin anhängare

Simplicio) mot det nya vetandet (representerat av Sagredo). Själv var han den opartiske

Salviati. I boken fäste sig Galilei bl a vid skillnaden mellan vad en tryckpump och en

sugpump kunde åstadkomma. Hans insats bestod i att han noterade den för alla sugpumpar

gemensamma gränsen: det går inte att suga upp vatten högre än 10 meter.

Enligt Aristoteles måste emellertid vattnet följa med kolven hur högt som helst!

Annars skulle ett vakuum uppkomma mellan kolven och vätskan, och naturen var rädd för

vakuum. Varför tar rädslan slut just när kolven dragit med sig en vattenpelare 10 m

upp? Är naturens rädsla för vakuum begränsad?

Galilei hade ingen teori att falla tillbaka på, och själv hann han inte formulera

någon. Han tog istället till en analogi från hållfasthetsläran. Alla vet att balkar,

som hängs upp i ena änden, kan knäckas av sin egen tyngd. Analogt menade Galilei att en

vattenpelare "upphängd" vid en kolv kunde knäckas av sin egen tyngd då

pelaren blev tio meter. I följande avsnitt ur "Diskussion om de två nya

vetenskaperna", diskuterar bara Sagredo och Salviati. Det blir tyvärr inte riktigt

rätt:

RISE OF WATER IN A PUMP

The interIocutors Sagredo and SaIviati have been discussing the explanation of tenacity by ascribing it to the existence of a vacuum between the small parts of a body, and the consequent striving of the parts of the body to approach nearer one another, because of the general principle that nature abhors a vacuum. Salviati has said that he accepts this view in part, but that he can prove that other causes are operative, and he describes an apparatus for that purpose.

SAGR. Thanks to this discussion, I have learned the cause of a certain effect which I have Iong wondered at and despaired of understanding. I once saw a cistern which had been provided with a pump under the mistaken impression that the water might thus be drawn with less effort or in greater quantity than by means of the ordinary bucket. The stock of the pump carried its sucker and valve in the upper part so that the water was lifted by attraction and not by a push as is the case with pumps in which the sucker is pIaced lower down. This pump worked perfectly so long as the water in the cistern stood above a certain level; but below this level the pump failed to work. When I first noticed this phenomenon I thought the machine was out of order; but the workman whom I caIIed in to repair it told me the defect was not in the pump but in the water which had fallen too low to be raised through such a height; and he added that it was not possible, either by a pump or by any other machine working on the principle of attraction, to lift water a hair's breadth above eighteen cubits; whether the pump be large or small this is the extreme limit of the lift. Up to this time I had been so thoughtless that, although I knew a rope, or rod of wood, or of iron, if sufficiently long, would break by its own weight when held by the upper end, it never occurred to me that the same thing would happen, only much more easily, to a column of water. And really is not that thing which is attracted in the pump a column of water attached at the upper end and stretched more and more until finally a point is reached where it breaks, like a rope, on account of its excessive weight?

SALV. That is precisely the way it works; this fixed elevation of eighteen cubits is true for any quantity of water whatever, be the pump large or small or even as fine as a straw. We may therefore say that, on weighing the water contained in a tube eighteen cubits long, no matter what the diameter, we shall obtain the value of the resistance of the vacuum in a cylinder of any solid material having a bore of this same diameter.

Du märker hur Galilei kämpar. Det är helt tydligt att han inte skulle kunna komma

vidare genom några mätningar - han har en helt felaktig utgångspunkt.

Det blev istället Evangelista Torricelli, som formulerade en hypotes, en teoriansats,

som var så fruktbar att den gick att verifiera och vidareutveckla genom mätningar.

Teorin gick ut på att vi lever omgivna av ett lufthav. Naturen är inte "rädd för

vakuum", men det finns ett lufthav, som trycker på och tränger in överallt, där

det annars skulle kunna bli tomt. Om denna teori var rätt - då skulle lufttrycket

gå att mäta. Det gjorde Torricelli. För att slippa att arbeta med höga rör använde

han kvicksilver i stället för vatten. Han vände ett provrör fyllt med kvicksilver upp

och ner i ett kvicksilverbad. Det visade sig då att kvicksilvret i röret sjönk till 760

mm ovanför behållarens kvicksilveryta. Detta tolkade han så att lufthavet tryckte mot

kvicksilverytan i behållaren med samma tryck som kvicksilverpelaren i provröret gjorde.

Han hade alltså uppfunnit barometern.

Bilden är hämtad ur Torricellis Samlade verk och visar hans

barometeransats.

Blaise Pascal blev näste man i kedjan. Om Torricelli hade rätt, tänkte han, då

måste lufttrycket vara lägre ju högre upp man kommer. Pascal var själv invalidiserad

sedan 18-årsåldern, men hans svåger Périer kontrollerade idén och beskrev sina

experiment och resultat i ett brev till Pascal den 22 september 1648. Först angav han

namnen på de herrar, som samlades i en trädgård nedanför berget Puy de Dome (höjd

1465 m). Sedan beskrev han förarbetet:

We therefore met on that day at eight o'clock in the morning in the garden of the Pères Minimes, which is in almost the lowest part of the town, where the experiment was begun in the following way :

First, I poured into a vessel sixteen pounds of quicksilver, which I had purified during the three preceding days; and taking two tubes of glass of equal size, each about four feet long, hermetically sealed at one end and open at the other, I made with each of them the ordinary experiment of the vacuum in the same vessel, and when I brought the two tubes near each other without lifting them out of the vessel, it was found that the quicksilver which remained in each of them was at the same level, and that it stood in each of them above the quicksilver in the vessel twenty-six inches three lines and a half. I repeated this experiment twice in the same place, with the same tubes, with the same quicksilver and in the same vessel; and found always that the quicksilver in the tubes was still at the same level and the same height as I found it the first time.

When this had been done, I left one of the two tubes in the vessel, for continual observation: I marked on the glass the height of the quicksilver, and leaving the tube in its place, I begged the Rev. Father Chastin, one of the inmates of the house, a man as pious as he is capable, who thinks very clearly in matters of this sort, to take the troubIe to observe it from time to time during the day, so as to see if any change occurred. And with the other tube and a part of the same quicksilver, I ascended with all these gentlemen to the top of the Puy-de-Dome.

Och slutligen kommer upplösningen: hur han väl uppe på berget fann att

kvicksilverpelaren i barometern stod lägre där. När han kom ner, fick han veta att

kvicksilverpelaren i kontrollbarometern i trädgården stått oförändrat högt.

Pascal var mäkta nöjd med resultatet och kommenterade:

This account cleared up all my difficulties and I do not conceal the fact that I was greatly delighted with it; and since I noticed that the distance of twenty toises in height made a difference of two lines in the height of the quicksilver, and that six or seven toises made one of about half a line, a fact which it was easy to test in this city, I made the ordinary experiment of the vacuum at the top and at the bottom of the tower of Saint-Jacques de-la-Boucherie, which is from twenty-four to twenty-five toises high: I found a difference of more than two lines in the height of the quicksilver; and then I made the same experiment in a private house, with ninety-six steps in the stairs, where I found very plainly a difference of half a line; which agrees perfectly with the account of Périer.

Du har nu fått en grundlig experiment - modell - teoribakgrund till varför man kan

använda lufttrycksbestämning vid höjdbestämning. En renlärig fysiker skulle kanske

komma på idén att bestämma höjden på en skyskrapa genom att mäta lufttrycket både

på marken och högst upp på skyskrapan. En mindre renlärig student såg andra

användningsmöjligheter för barometern när han skulle bestämma höjden av en

skyskrapa:

Some time ago I received a call from a colleague who asked if I would be the referee on the grading of an examination question. He was about to give a student a zero for his answer to a physics question, while the student claimed he should receive a perfect score and would if the system were not set up against the student. The instructor and the student agreed to an impartial arbiter, and I was selected.

I went to my colleague's office and read the examination question: "Show how it is possible to determine the height of a tall building with the aid of a barometer."

The student had answered: "Take the barometer to the top of the building, attach a long rope to it, lower the barometer to the street, and then bring it up, measuring the length of rope. The length of the rope is the height of the building."

I pointed out that the student really had a strong case for full credit, since he had answered the question completely and correctly. On the other hand, if full credit were given, it could well contribute to a high grade for the student in his physics course. A high grade is supposed to certify competence in physics, but the answer did not confirm this. I suggested that the student have another try at answering the question. I was not surprised that my colleague agreed, but I was surprised that the student did.

I gave the student six minutes to answer the question, with the warning that his answer should show some knowledge of physics. At the end of five minutes, he had not written anything. I asked if he had given up, but he said no. He had many answers to the problem; he was just thinking of the best one. I excused myself for interrupting him, and asked him to please go on. In the next minute he dashed off his answer which read: "Take the barometer to the top of the building and lean over the edge of the roof. Drop the barometer, timing its fall with a stopwatch. Then, using the formula s=1/2 · (at2), calculate the height of the building."

At this point, I asked my colleague if he would give up. He conceded, and I gave the student almost full credit.

On leaving my colleague's office, I recalled that the student had said he had other answers to the problem, so I asked him what they were. "Oh,yes," said the student. "There are many ways of getting the height of a tall building with the aid of a barometer. For example, you could take the barometer out on a sunny day and measure the height of the barometer, the length of its shadow, and the length of the shadow of the building, and by the use of simple proportion, determine the height of the building."

"Fine," I said. "And the others?"

"Yes," said the student. "There is a very basic measurement method that you will like. In this method, you take the barometer and begin to walk up the stairs. As you climb the stairs, you mark off the length of the barometer along the wall. You then count the number of marks, and this will give the height of the building in barometer units. A very direct method."

"Of course, if you want a more sophisticated method, you can tie the barometer to the end of a string, swing it as a pendulum, and determine the value of 'g' at the street level and at the top of the building. From the difference between the two values of 'g', the height of the building can, in principle, be calculated."

"Finally," he concluded, 'there are many other ways of solving the problem. Probably the best,' he said, "is to take the barometer to the basement and knock on the superintendent's door. When the superintendent answers, you speak to him as follows: 'Mr Superintendent, here I have a fine barometer. If you will tell me the height of the building, I will give you this barometer.'"

At this point, I asked the student if he really did not know the conventional answer to this question. He admitted that he did, but said that he was fed up with high school and college instructors trying to teach him how to think, to use the 'scientific method' and to explore the deep inner logic of the subject in a pedantic way, as is often done in the new mathematics, rather than teaching him the structure of the subject. With this in mind, he decided to revive scholasticism as an academic lark to challenge the Sputnik-panicked classrooms of America.

Ur: The Saturday Review, 21/12-68.

Hemsida | Sök på servern | E-post till Webmistress | Personal och adresser